Summary of chapter 1: Maran Rosh HaYeshivah HaGaon HaRav Baruch Sorotzkin zt”l fled with friends from the Kaminetz Yeshivah to Telshe, traveling through Lodz where his sister, Tema Zajdenworm lived. His cousin, Rosh HaYeshivah HaGaon Rav Avraham Yitzchak Bloch Hy”d, arranged the necessary paperwork for him to remain in Telshe and suggests that he marry his daughter Rochel. Rav Baruch at first deliberates if he should flee as fast as he can because of the war.

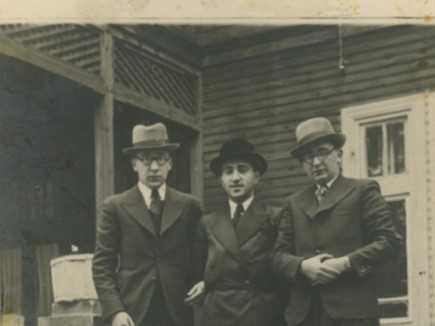

His father, Rav Zalman Sorotzkin, arrives in Eretz Yisrael after a difficult journey and sends a telegram to Telshe suggesting that Rav Baruch accept the shidduch suggestion. Right after their marriage, the young couple, their brother Rav Eliezer, and their cousin Chasya, join a group of Telshe and Mir yeshivah students who succeed in receiving transit visas that enable them to cross the Russian border and escape. Before they board the Trans-Siberian train, Rav Avraham Yitzchak tells his new son-in-law and daughter that during their travels and wanderings they should adhere to the yeshivah life, and they succeed in keeping sedarim as if they weren’t in the midst of a miraculous flight.

Suddenly, they stopped hearing from them.

The last letter was sent during their journey from Lithuania to Vladivostok.

The atmosphere in the Sorotzkin home in Yerushalayim was dreadfully strained. A few weeks earlier, a few days after Rav Zalman Sorotzkin and his wife reached Eretz Yisrael together with their two young twin sons, the skies over Tel Aviv trembled.

The Royal Italian Air Force bombed the city.

Prime Minister of Italy, Dictator Benito Mussolini, joined the Nazi war against the British, whose empire included Eretz Yisrael at the time. The Jaffe port was attacked, and the fires caused by the shelling were seen from afar. Over 100 Jews were killed in Tel Aviv during the attack. Jewish blood was being spilled like water everywhere, even in Eretz Yisrael. The situation was frightening, and the Jews killed in the attack were buried in a mass grave.

The residents in Eretz Yisrael were being closed in by their enemies on all sides. The Nazi threat of capturing Eretz Yisrael was realistic. The Vichy Government in France, which sided with the Nazis, ruled over Syria and Lebanon, permitted the German Nazi pilots, the Luftwaffe, to base themselves in these countries, taking off, landing, refueling and maintaining the planes used when attacking.

A few days later, British pilots set off on a mission of revenge, bombing Rhodes and Leros, islands under Italian rule, and from where the planes that had attacked Tel Aviv had taken off.

But the Sorotzkin family and other Jews weren’t relying on the air force or any other type of physical force. They all knew that back at Har Sinai sinah, hatred, came down to this world, and that in every generation our enemies stand against us to destroy us and Hakadosh Baruch Hu saves us from their hands.

Almost two years later, the situation seemed hopeless. The Nazis threatened to invade from the north and south and were not too far from gates of Eretz Yisrael. In Yerushalayim, the shuls were full of people davening, their hearts crying out to Hashem.

HaGaon HaRav Meshulem Dovid Soloveitchik zt”l gave a moving description. At the peak of the tearful tefillos, when everyone was pleading to Hashem to take pity on the few survivors, Rav Zalman Sorotzkin went up to the bimah and cried out, “Ribbono shel Olam, You wrote in Your Torah, “Gam zos beheyosem b’eretz oi’veihem lo miastim v’lo gi’altim l’chalosm…- Even when you are in the land of your enemies I will not be revolted by you and will not renounce you and obliterate you.” If these evil people reach Eretz Yisrael wouldn’t that express that You found us revolting, that You obliterated us?”

His chilling words were followed by screams and cries, as heartfelt tefillos ascended from every corner of the shul. Who knows what those pure, authentic tefillos accomplished? A few months later, it was clear to everyone that Hashem protected the residents of Eretz Yisrael with miracles. In direct contrast to the explicit commands he received in Egypt, the evil German general fled through the desert. There was very little left of the giant divisions that had conquered great territories. Only a few tanks were left.

But now, the family was waiting to hear word from their children and the group of Telshe talmidim that had left for the Far East.

A little while earlier, at the end of a long, exhausting trip on the Trans-Siberian Railway, that made its way from Kovno to Vladivostok, cutting through a number of time zones, the yeshivah students arrived at the port, where a small Japanese ship was waiting for them. It was too small, but they crowded onto the vessel. Suddenly, after days of tension and escape, they looked at the approaching land, hoping for a chance to rest.

This was Kobe, one of the biggest Japanese port cities. There they were surprised to meet Jews who greeted them happily, who wanted to take care of them, to host them in their homes and to cook them limited amounts of kosher food.

One in Kobe, they started sending letters again. True, they stuttered and stammered, but at least they were in touch. The refugees sent a few letters at the same time, hoping that at least one of them would reach its destination.

Right before Nissan, an unexpected luxury arrived. Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, head of Yeshivas Mir and a leader of the Vaad Hatzalah in the United States, who had learned in Telshe, succeeded in sending large amounts of matzah and wine to Kobe. The refugees were astonished. At the height of the war, Hashem sent them abundant food supplies for Pesach.

They knew that, more than ever, they were obligated to shoulder the yoke of Torah. This is what feeds the victory of the Jewish nation, the rabbim were overpowered by the me’atim, because of the few who were oskei Torasecha. And so they established batei medrash at the end of the world. In Kobe, a location so uncertain that its relationship to the international dateline is unclear, they encountered a halachic question that nobody ever thought would need clarification: When is Shabbos? (See in-depth discussion)

But even there, the ground trembled under their feet. The visas they had received from Sugihara were nothing more than a trick, transit visas that allowed them to leave Lithuania. They had declared that they would travel through Japan, on their way to the Dutch-controlled island of Curação, and their transit visas were valid for a few short weeks. The local Jews negotiated tirelessly with the Japanese government who wanted to expel these Jewish “tourists.” Time after time, they succeeded in extending the validity of the visas, by promising that the group would soon continue their journey out of the country.

When the group had started their journey, they had hoped that the United States would help them. But their hopes were in vain.

The American consul in Kobe drowned them in a sea of rigid bureaucracy, including obstinate insistence that they present affidavits from United State citizens guaranteeing that they would provide for the refugees.

“In Yokohama,” the rumor spread, “the American consul is more considerate.” One after the other, the yeshivah students travelled to that city, which was located near Tokyo, the capital of Japan. There they discovered that though the consul was more empathetic, they had to contend with a new decree: The United States government rejected visa requests from anyone with relatives in enemy countries like Russia or Germany, since the refugees were liable to stay in contact with their families in these enemy countries. That meant that most of the bachurim were no longer eligible for a visa. But there was a solution: They could make false declaration and conveniently forget about family members. For Rav Baruch and Rav Eliezer that meant they needed to make sure that nobody would find out about their older brother Rav Elchonon and their sister Tema, who were in Russia and Lithuania.

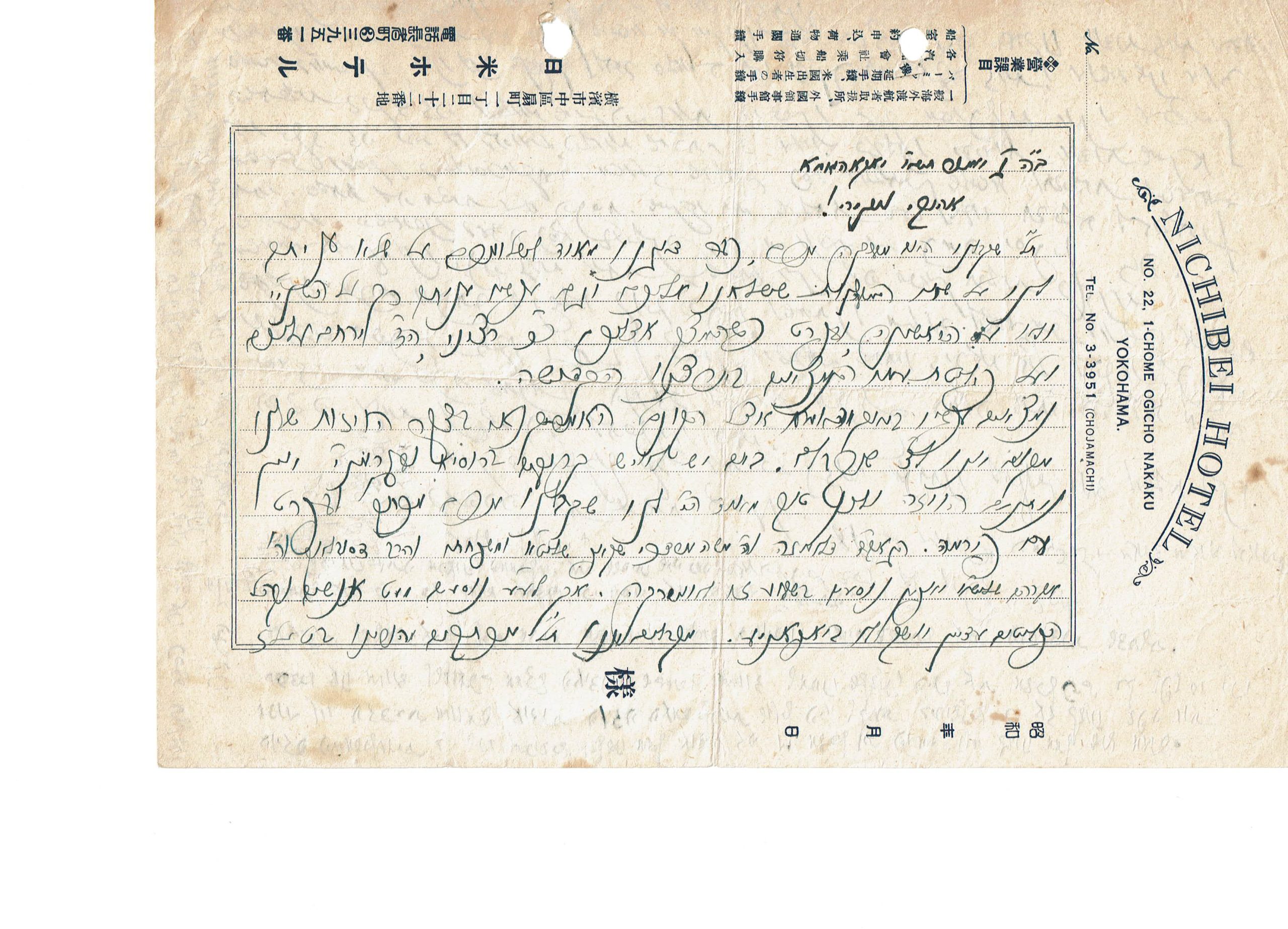

During their first visit to Yokohama, they sat in the lobby of Nichibei Hotel, which was located across from the consulate. The hotel was the preferred resting place for all yeshivah students in the city.

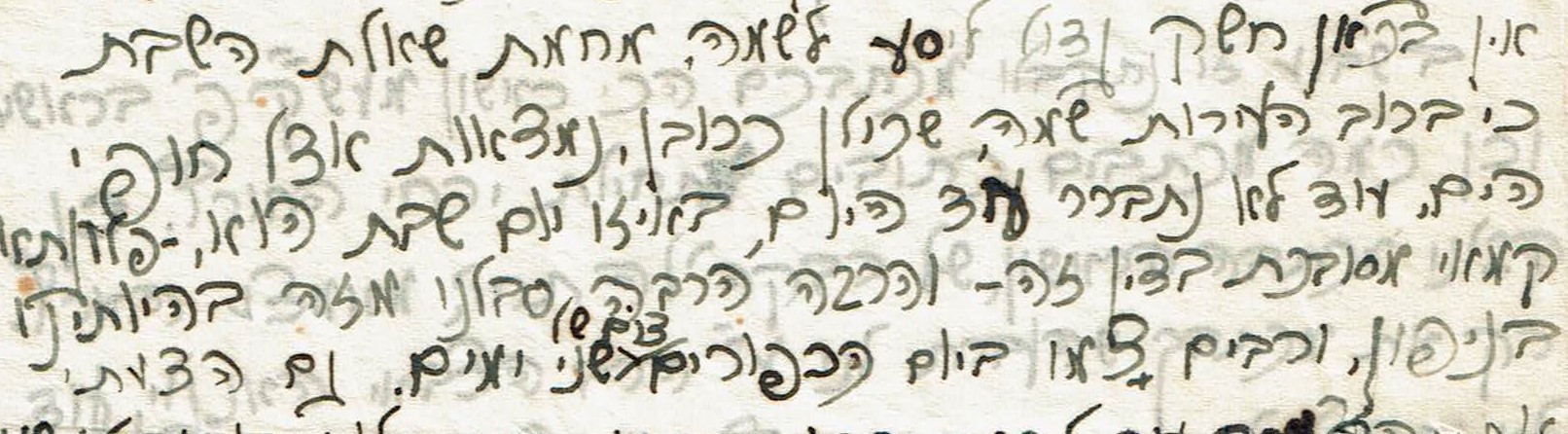

They wrote long detailed letters on the official letterhead of the Nichibei Hotel in Yokohama. These papers bear Japanese words printed from top to bottom. (Japanese is read from left to right, but in newspapers, books and official documents, it’s read from top to bottom.) To match the top-to-bottom print, the lines on the letterhead were printed vertically. The yeshivah students turned the leaf on its side, filling in the lines and using every inch of empty space on the page.

That day, they had received a telegram from Yerushalayim. Rav Baruch took his pen and started to write:

“Dear loved ones!

Baruch Hashem, we received your telegram today. We were very worried because you didn’t answer the other letters we sent. Now you only answered the second letter, and not the first one. We’re particularly worried, because your situation is so grave. May Hashem have pity on you, and on the remnants of His nation located in the Holy Land.

“We are now in Yokohama by the American consulate regarding our visas. We daven that Hashem helps us receive them. If we have relatives in Russia or Germany, they won’t issue them… The Rav of Lomza, Rav Moshe Mordechai Shkop shlita and his family are traveling to America this week. (He was the son of Rav Shimon Shkop, who took over his father’s rabbinate in Grodno until war broke out, and then he fled to Vilna. He traveled with the yeshivah students from Vilna, and then continued on to the United States). But, as of now, only a few people are traveling, and the group of refugees is still living in Japan.”

In this letter, Rav Baruch reveals that he’s still in contact with Telshe. It was just a few months before the rabbanim and talmidim in Lithuania were killed al kidddush Hashem. The letter indicates the efforts made in Japan to try to rescue his father-in-law, HaGaon HaRav Avraham Yitzchak Bloch.

“Baruch Hashem, we receive letters from our parents in Telshe and we are trying as hard as we can to save them, and if only Hashem will help us…We can make him shlita citizenship, but we don’t have the necessary funds. We sent this information by telegram to our uncles shlita in America, and they told us to send it to Rav Silver. We don’t understand this answer, we are doing our hishtadlus in this area, and we hope we will succeed…If only Hashem will have pity on us.”

Through these tidbits, the refugees in Yerushalayim collected fragments of information about family members scattered around the world.

Rav Baruch concluded his letters with words of hope; like the following words that he wrote in the lobby of the Japanese hotel, “May Hashem gather the scattered members of our family and send Mashiach Tzidkeinu bi’miheira. Your son and brother who misses you very much and longs to see you.

Baruch.”

Later on, Reb Eliezer added a few lines in the margins of the leaf and fills its border. His words express his agitation and despondency.

“My dear loved ones, we just returned from the American consulate after a few hours. I am making do with just a few words, because I’m traveling “home” to Kobe. Once there, I will send a detailed letter by airmail.

We are very worried about you in Eretz Yisrael and the letter we received today made us very happy…

I will write in detail in Kobe, and may Hashem soon gather our scattered remnants. You loving son, Eliezer.”

In a short line, they describe their longing and worry for their older brother, who was left behind in Europe:

“In regards to Elchonon shlita: We are trying everything we can through Rav Silver and the Vaad Hatzalah to facilitate his rescue. Unfortunately, we haven’t received an answer yet.”

Rebbetzin Rochel a”h: “Mother, don’t worry about me. What’s happening by you? “

Rav Baruch intended to include a lengthy letter that his new wife, Rebbetzin Rochel, had written to her father and mother-in-law, but it was mistakenly left in Japan. The next letter explains that the uncertain conditions and upheaval caused the letter to be forgotten. “Don’t worry about me, Mommy,” Rebbetzin Rochel calms her mother-in-law. “Baruch Hashem, I feel well. When I am with Baruch, I don’t lack anything, even though I miss my dear parents very much, and I’m waiting for us to all meet in peace.”

And then, as if they weren’t in danger themselves, as if they weren’t wandering in Japan, she describes their situation in glowing terms and sends encouragement to Yerushalayim:

“How are you, my beloved ones? We have recently started to worry about you.

“Who knows what the situation is like by you? But we must trust in Hashem that He will not abandon us and will not remove His hashgachah from you. We sent you two telegrams without receiving replies, so we got very worried. But now that we received a response from you, our eyes lit up again.

“We are managing here very well…Chasya, the daughter of Rav Eliyahu Meir, and me. We rented three rooms that cost very little. Our home is not too far from the sea, and the air is clear and healthy. Chasya and I have learned how to cook and we have turned into serious housewives. We often invite guests to our home.

“One Shabbos, we had the family of Rav Shmuel Dovid Walkin for three meals (son-in-law of Rav Moshe Londinsky, Rosh Yeshiva of Radin; son of Rav Aharon Walkin, Rav Zalman’s brother-in-law. He and his wife left Vilna with the yeshiva students. They were the only members of their entire families to survive the war). We pass the time pleasantly. We just accompanied Leizer to Yokohama, and are waiting for an answer from the consulate regarding a visa. We hope for a positive response.

You can see, dear parents, that there is no reason to worry about us.”

This letter was also written on the hotel’s letterhead. In a tiny empty space on the page, one of the yeshivah students sent an appeal to his parents, asking them to send “proof” that he doesn’t have any relatives in enemy territory.

“Dear HaRav HaGaon HaMefursam …Zalman Sorotzkin shlita,” wrote the bachur, Tuvia Lazdon. “I am asking from your honor, to please ask the Lazdon family at 40 Balfour Street in Tel Aviv to immediately send me a letter with the addresses of all my brothers and sisters who have been living in Eretz Yisrael for the past two years, because the American consulate demands proof, and that my parents (Reb Yosef and Maras Rochel) write to me. He doesn’t believe me and claims that they live in Germany, and won’t give me a visa. Also, please send a telegram with the names of…”

Thank you…”

These letters provide a whiff of the mood during those times, days when they all shifted between hope and despondency, battling for their life with money and the vagaries of bureaucracy.

Stressed and worried, Rav Zalman sent a letter to his nephew, Rav Eliyahu Meir Bloch, who had traveled to the United States on behalf of the yeshivah together with his brother-in-law, Rav Chaim Mordechai Katz—a trip that saved their lives. He questions if he and his children had been forgotten under piles of bureaucracy.

“Our hopes regarding the promises from Washington have not been fulfilled…” Rav Eliyahu Meir responded by describing the great efforts being made on their behalf; efforts which, until then, had been futile. “The words of our uncle shlita, ‘Why are we not trying to get visas for them,’ expresses an unfounded suspicion. It is our greatest desire to procure visas for the yeshivah talmidim, of course we are also trying to get visas for Baruch, Eliezer and Rochel! Things are going slowly. Baruch Hashem, Baruch and Rochel already received visas due to the transfers we procured for them. And Eliezer and Chasya were promised that they will receive them very soon.

“If the order of this world doesn’t change, we can hope to see them soon. My mood right now…there is nobody to rely upon other than our Father in Heaven, that He have pity on all our dear ones…and save them from sword and captivity.”

All our toil to immigrate to the United States is like a fleeting dream

As time passed, disappointments piled up. “All our efforts to immigrate to the United States is like a fleeting dream,” they wrote in a painful letter. They finally procured confirmation that their visas were written and signed…but then a new decree regarding those who signed the affidavits in the United States, turned the visas that were on the way into worthless pieces of paper. They would need to start the whole process again.

There was one ray of light: Rebbetzin Rochel, Rav Baruch’s wife, received her visa. Every visa request was placed on a waiting list for the immigration quota for the country in which the person was born. The Rebbetzin was born in Kharkov, and the waiting list for Russian immigrants was shorter than for those born in Poland.

Rav Baruch and his brother received their visas two days later. But those two days were the difference between freedom and disappointment. The law changed and their visas went to the garbage. “All of our toil has been wasted and we need to start again, to renew the request and have Washington approve them,” they wrote.

“When the consul receives an answer from Washington indicating that they will allow us to enter their country, we’ll need to be interrogated again by the local consul. Then he either approves or rejects the visa. The consul in Yokohama promised that if we receive our visas from Washington, he won’t make any problems for us and will expedite our visas. Despite this, it will take a few months, especially for us, to have the documents approved in Washington again…We need to swear and confirm that everything we said by the local consul is true, and because of the decree regarding relatives in Russia and Germany, almost nothing we said by the consul coincides with the truth.

“We need to make sure that the testimony is synchronized amongst all of us; that which is said in Japan, that which is said in Eretz Yisrael, and perhaps that which is said in the United States — if Rebbetzin Rochel chooses to travel alone, instead of waiting a long time until they succeed in rearranging our visas. And then, who knows, what will happen to her visa?”

“Perhaps they will interrogate you at the American consulate in Yerushalayim regarding us and our siblings,” they write to Rav Zalman. “Please say that you have four sons. Disown Elchonon and Tema; one of the main reasons America refuses visa requests is because of relatives in Russia or Germany. At the consulate in Yokohama, we said that Father and Mother and my two brothers are in Eretz Yisrael. I ignored Elchonon and didn’t mention a sister. You must know what to say if you are called into the consulate and asked questions about us. Rumors have spread that since the new law was enacted in Washington, they examine and verify the truth of the applications, and it is possible they will ask you questions through the consulate in Yerushalayim.”

In addition, he suggests that if for some reason they already said something about their children to the consulate in Yerushalayim, they should finish the arrangements in the consulate in Tel Aviv.

“This step is not hard for us,” Rav Baruch explained. “It is the truth, even if we didn’t mention Elchonon shlita and Tema. Who said that I need to have more than three brothers? The American consulate might ask you questions because of the new procedure in Washington, so please remember this. For Rochele techiye this is harder, because if they ask her…We said that he (her father, Rav Avraham Yitzchak) is in Eretz Yisrael, but they might ask for proof.”

Yeshivas Telshe-Japan

The Japanese understood that if they didn’t take action, the yeshivah students would stay exactly where they were. So, they announced that they were expelling them to China, to the ghetto in Shanghai, an area established in the Chinese city that was then under Japanese rule.

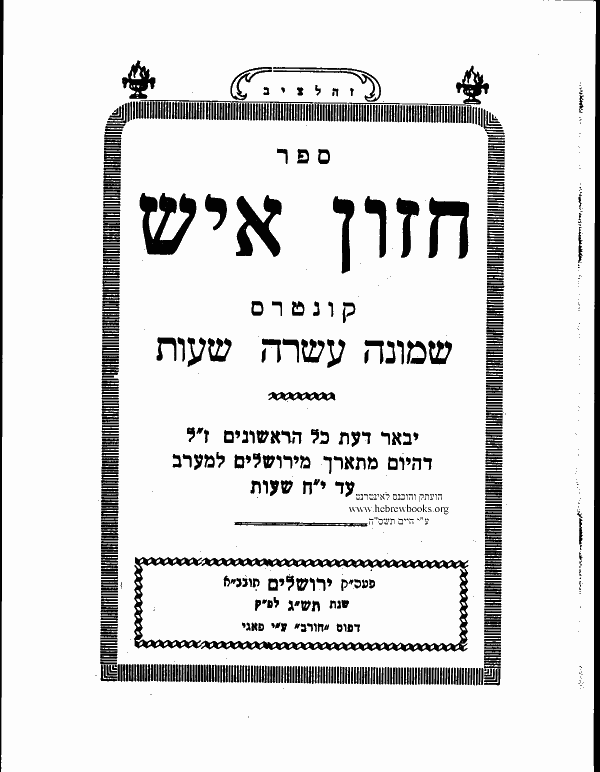

Despite the upheaval and the attempts to immigrate, the heads of the Telshe yeshivah students and Mir Yeshivah students were fully immersed in Torah. In Kobe, they took advantage of the accessibility of a Jewish-owned press and printed the sefarim they needed. In Shanghai, they operated a whole industry of printing sefarim.

They printed Chumashim, Shas, Ketzos HaChoshen, Shev Shmaisa, Shita Mekubetzes and Shu”t HaRashaba, one right after the other. They didn’t forget the importance of sifrei mussar, and printed the Ohr Yisrael and, of course, the Shiurei Daas that buoyed the mood of the talmidim of Telshe, who reveled in the sichos of Rav Yosef Leib Bloch zt”l. During that period of time, the Shanghai edition of many seforim were printed. They had to come up with techniques and ideas in order to print the Hebrew letters— but they would do anything and everything to keep the kol Torah strong.

As they prepared to travel from Japan to China, they already had a number of printed seforim and an official letterhead of the wandering Telshe Yeshivah that had been printed in Kobe. The official letterhead bore the name of Rav Baruch Ben HaGaon Rav Zalman shlita Sorotkzin – kibbutz hatalmidim of the Yeshivah HaGedolah V’Hakedosha Etz Chaim in Telshe, Kobe-Shanghai.”

Rav Eliezer wrote the last letter from Japan with a notice about their upcoming move to their new location, on Erev Shabbos Parshas Re’eh.

He wrote, “Naypon,” meaning Japan, at the top of the page.

“Dear Loved Ones!

“A few weeks have passed during which we haven’t received any information from you, though we recently received mail from Eretz Yisrael. We are very worried about you. The dearth of letters surprises us, because we’ve gotten used to receiving your letters in a frequent, orderly fashion, in every post from Eretz Yisrael. What changed?

“We consoled ourselves with letters from Rosh Yeshivah shlita and the Kriniker Rav, who are located in Eretz Yisrael at this time and mention you in their letters. Your letters must have gotten lost in the mail. We are in the same situation as you, for it seems that our previous letters got lost on their way due to the upheaval and disorder of our times…

But please, when you receive our letters, answer us immediately by airmail, to calm our agitated spirts. We have almost completely given up on our trip to the United States…time will tell.”

He then shares a piece of information: Rav Baruch received a Canadian visa and he is a candidate for a Paraguayan visa. “The truth is that that I have no desire or wish to wander and travel so far away from the Jewish community. Currently, there are only about 300 Jews living in Paraguay. I want to travel to Eretz Yisrael, and finally mend the tears in our family. I would like to hear your opinion, that will decide if I should turn right or left.”

Then he informs them:

“In a few days, we will be forced to leave Japan and travel to Shanghai. Shanghai is the only city in the east from which we can still leave to other places in the world. Due to the conditions in the east today, Japanese boats no longer travel to the Near East or the United States, only from Shanghai, because it’s a free city. From time to time, ships set sail from there to the four corners of the world.”

“Please send your response to the address of Rav Ashkenazi, av”d over there. He is originally from Chisławiczi and is a relative of ours, a relation of Rav Henkin of New York. He knows and has clear memories of our grandfather Rav Bentzion zt”l. He has served as Rav of Shanghai for over thirty years.”

This is a reference to Rav Meir Ashkenazi, a talmid of Yeshivas Tomchei Temimim Lubavitch. Rav Ashkenazi served as rav in a number of cities. When he traveled through Shanghai on his way to the United States, he was asked by local Jews to remain in their city. He remained at his post in Shanghai for two decades, until he moved to Eretz Yisrael.

In the margins of this letter, he writes disturbingly that they had completely lost contact with their sister, Mrs. Tema Zajdenworm in Lodz. Rav Elchonon’s wife, who had remained in Vilna after he was arrested by the Russians and sent to Siberia, managed to send them a letter saying that her husband sent letters from Siberia saying that he was doing fine.

However, she asked them not to write to him because of the danger. She also asked about Tema, because she hadn’t either received any letters in Vilna. In those days, they still didn’t understand the scope of the atrocities and didn’t realize that there was nobody left to send them letters from Lodz.

“There’s no news over here,” Rav Eliezer concludes his letter. “I sit and learn. Baruch is busy organizing and learning with the Telshe talmidim who are here…”

Like Rav Eliezer wrote, the fact that the yeshivah continued on, even during this stormy period wasn’t news at all. It was the essence of the yeshivah talmidim. The enemies of Klal Yisrael were trying as hard as they could l’hashkicham Torasecha, to have them forget the Torah, but they continued learning, day and night, without stopping for a minute. The yeshivah was entrenched within them and wandered along with them wherever they went.

What difference did it make, whether they were in Lithuania or Japan, on a train or in China?

Shteigen is shteigen, and if they need a Rambam…they made sure to print it.

Thanks to Bein Hadeah Vehaddibur and Rav Michoel Sorotzkin shlita for allowing us to use the letters and their history.

Twice Shabbos: “We suffered a lot and many fasted twice for Yom Kippur

Kobe is located about 100 degrees of Eretz Yisrael which generated an expansive polemic regarding its halachic timeframe, a problem that primarily reared its head on Shabbos. Some poskim are of the opinion that the Jewish dateline is located about 90 degrees from Yerushalayim, which means that Shabbos in Kobe starts when its already Sunday in Eretz Yisroel. However, other poskim hold that the Jewish dateline is 180 degrees from Eretz Yisrael, which means that Shabbos in Kobe is exactly the same time as Shabbos in Eretz Yisroel.

This machlokes existed since the times of the Rishonim, so before they even left Vilna, some talmidim asked the Brisker Rav what they should do. He answered that Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spector hadn’t issued a psak on the question, saying that he couldn’t decide between Rishonim; and if Rav Yitzchok Elchonon wouldn’t give a psak, he wouldn’t either. The Brisker Rav suggested that they ask the dayan of Brisk, Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer, to decide the shaila for them. Rav Simcha Zelig wrote a number of teshuvos, the gist of his idea being that since Shabbos was accepted over there on the seventh day, they chould rely on that. However, since Shabbos over there is on Sunday, they should refrain from doing issurei d’Oraysa and should say “gut Shabbos,” which, according to Rav Akiva Eiger, is like making kiddush.

Rav Yechezkel Levenstein, the Ohr Yechezkel, Mashgiach in Mir, said that this situation was like “ilmalei mishamrin Yisrael shtei Shabbasos.”

“This Shabbos is a spiritual revolution,” Rav Eliezer described how they observed Shabbos in one of his letters. “Until now, we were mekadesh shabbos like all European diaspora on Shabbos. But last week, we received a telegram from the Chazon Ish in Bnei Brak, informing us that we should be mekadesh Shabbos like they do in the United States: The following day, on Sunday. Since until now, we kept Shabbos like they do in Europe, we are now machmir and are mekadesh “two Shabbosos.”

That Shabbos, which according to the Chazon Ish was really Friday, Rav Yechezkel Levenstein entered the beis medrash and start davening the weekday Maariv.

As Yom Kippur approached, it was decided to ask the Gedolei Yisrael of Eretz Yisrael to decide when and how the group in Kobe should observe the day.

An urgent telegram was addressed to the Brisker Rav, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, the Gerrer Rebbe, Rav Chizkiyahu Mishkovski and Rav Yitzchak HaLevi Herzog: “350 Jews are begging; save us, answer quickly: Which day should we fast on Yom Kippur? Agudas Rabbanim and Baalei Batim in Kobe.”

The Brisker Rav asked Rav Finkel to issue a psak for his talmidim, because he still didn’t want to pasken.

The Rabbanim met in Yerushalayim and Rav Herzog sent a response: “In response to your telegram, the meeting of rabbanim decided that Wednesday is the fast of Yom Kippur, according to the calculation in Japan. I am adding the note that you should not fast an additional day, on Thursday, because of the danger. But you should act on Thursday as explained in the Shulchan Aruch Orech Chaim (siman 618 se’if 7-8) (eating less than a shiur etc.).

The Chazon Ish heard the psak and was of the opinion that it was a compromise that was liable to cause the group in Shanghai to lose out twofold: They would miss the mitzvah of eating on the eve of the fast and the mitzvah of fasting. He sent a short telegram to Japan: “Dear brothers, eat on Wednesday and fast on Yom Kippur on Thursday. Don’t worry about anything.”

(It is generally believed that the Brisker Rav agreed with the Chazon Ish but didn’t sign on the letter, because he was scared that some people would be machmir and would fast for two days in a row, endangering their lives. In fact, some bachurim did fast for two days straight, in order to fulfill the obligation to fast according to all opinions.)

Later, when the refugees were still in Shanghai, Rav Zalman tried to make arrangements for his son to travel to Australia. But his son wrote back that he doesn’t want to go there, “In most villages, most of which are located on the shore, it is still not clear which day is Shabbos.” He writes that there’s a machlokes Rishonim about the dateline, and it was a big discussion when he was in Kobe, Japan. “We suffered a lot from it when we were in Japan and many fasted for two days on Yom Kippur,” he added.

When they moved to Shanghai, at least they no longer had to deal with this uncertainty.